Popularized in Italy, so-called “mask culture” dates way back to before the 12th century. Venice—once the capital of the Venetian Republic—is known by many names, the most interesting being “The Masked City.” According to a video essay from medieval YouTuber “Metatron,” the city was a huge international financial center and is the birthplace of the Venetian Carnival.

Masquerading became incredibly popular in 12th century Italy, with enthusiasm regarding the annual Venetian Carnival booming in the Medieval Era. During this carnival season, people dressed up in traditional clothing and wore masks out and about. These masked gatherings were intended to be a celebratory space, free from the shackles of societal expectations—an inclusive festival which allowed people from different backgrounds to mingle, unbothered by economic disparities.

This culture quickly spiraled, and according to an article from the London Museum, people in Venice wore masks daily to conceal their identity while engaging in prohibited or shunned activities. The mask allowed for people to engage in taboo activities like gambling, and women could wear what they wanted without the fear of being publicly shamed.

Because of this masked culture, citizens felt comfortable speaking their minds in public and didn’t fear any repercussions. Everyone had a voice, and everyone was able to hide behind the mask of anonymity to express the socially not-so-acceptable parts of themselves.

Masquerade balls in fictional stories traditionally depict sultry settings, where the royal falls for the pauper. And believe it or not, this idea does have a grounding in reality—such balls did allow for the poorer sectors of society to escape poverty for a short while, feeling as though they were equals to their high society counterparts.

Masquerade balls as we know them were popularized in 18th century London according to the London Museum, drawing on the appeal of luxurious mystery to engage an exclusive crowd.

While public masquerades were still a buzzing phenomenon, the elitist side of masquerades was heavily embraced by aristocrats and royalty, using masquerade balls as more than just parties. These were lavish displays of luxury, wealth and art. They allowed for spaces where royalty could shed their public image and high society standards, engaging in sensual behavior, scandalous-ness and gossip.

Masks were once a symbol of festivities and celebrations—of freedom of speech and being oneself. Now, though, they have now evolved to hold many different meanings. For example, we use masks to hide who we truly are; quite counterintuitive given that masks were once used to promote self-indulgence and expression.

Using physical and metaphorical masks in modern day helps to hide the parts of us that we feel disgust for, be them facial features hidden with makeup and surgeries or parts of our body that have been deemed “unattractive” by society. There are parts of our personality that others may find hard to digest, and thus we find them so as well, banishing them and neatly tucking them away in the face of expectations that we hold ourselves to.

Technology has not helped with this phenomenon. The rise of social media has provided a platform for individuals of all age groups from all over the world to partake informally in a variety of cultures and subcultures, carefully curating their own digital personas so as to be perceived in a way that they desire.

People pose to be rich online to feel better about their lives and escape their “lesser” reality. The internet has always been a place of escapism—a metaphorical mask—which allows one to perform their identity.

And in a version of the world that is fighting to be more accepting, why do we struggle so much with authenticity? Why are we constantly trying to socially one-up each other when instead we could be supporting one another? Why do we all want a village but never want to be a villager?

Today, almost everyone wears a mask whether they realize it or not. Be it big or small, colorful or black, sheer or opaque, our performances only put us in boxes.

It’s a dangerous dance—we vie for external validation, still falling victim to the insecurities that we tried to mask in the first place. Instead of being freed from social norms, we end up feeding into them.

Just as masquerade masks are tediously crafted from different materials and are often intricately and intentionally made, so are we. What starts as natural exploration can quickly fall victim to performance art, masking from the world in a way that simultaneously protects and damages ourselves.

When something is worn so often and so well, it’s easy to forget that it’s even there. Take a look in the mirror; can you still take your costume off, or is it a part of you?

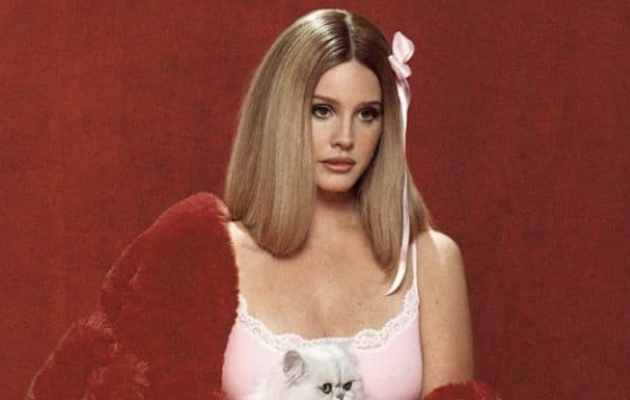

SHOOT LEAD Summer Neds / PHOTOGRAPHERS Maylatt Eyassu, Sierra Hudson, Yu Liu / MODELS Aliyse Stokes, Hala Alyounes, Kallyn Buckenmyer, Kelsie Goane, Mia Robinson, Michelle Cai, Summer Neds, Yaashita Bobba / STYLIST Emerson Lepicki / HAIR & MAKEUP Hala Alyounes